- Home

- Suzanne Nelson

Serendipity's Footsteps Page 12

Serendipity's Footsteps Read online

Page 12

“Okay,” Bea said, then giggled as her mother scooped her into a tickling hug.

For months since then, Bea had lost herself in the maze of rooms. It was easy to pretend she was the stone princess here. Just like she was doing tonight, as the jumble of shoes and loud voices invaded her hiding place.

The lace tablecloth dipped down to the floor, giving Bea the perfect unseen refuge underneath.

After her mother had tucked her into bed, Bea had waited until she’d gone to dress for the dinner party, then tiptoed downstairs. Slowly, the dining room had filled with guests, and laughter and the tinkling of china rang in the air.

A pair of lemon-yellow high heels appeared at the edge of the tablecloth now, followed by a pair of blue ones with pink-painted toenails peeking out of the tips.

“This place is incredible. Twenty acres. A driving range, a pool atrium out back,” whispered Lemon Shoes. “Evie has quite the catch. It was worth the drive from Ohio to see all this.”

“Oh yes,” Pink Toes said. “Benjamin’s worth millions. Evie certainly found her safety net.”

“Well, she deserves it after losing Robbie,” Lemon Shoes said. “He was the love of her life.”

“I heard that after it happened, Evie wouldn’t leave her bed for weeks.” Pink Toes was whispering. “Her mother nearly had her committed. And there was the poor little girl, wandering around the house, practically orphaned. But Evie pulled through.”

Bea clutched her doll tighter, tears welling up under her eyelids. She remembered the bad time. When her mother had met Benjamin, though, she’d stopped wearing her bathrobe every day. She’d stopped crying, too. And now she was always smiling. But her smiles were plastic like a doll’s. They weren’t like the smiles she used to give Daddy.

“Well, it was such a tragedy,” Lemon said. “A heart attack at thirty-two. It doesn’t even seem possible.”

Bea’s eyes wouldn’t stay frozen anymore. Tears streamed down her face, and there was a sob inside her threatening to burst out.

Pink Toes made a tsk-tsk sound. “He fought in the war. Who knows what that could’ve done to his heart?”

“Bad hearts can run in families,” Lemon said. “If I were Evie, I’d have that little girl examined by a doctor right away.”

The sob ripped out of Bea’s throat, and she brought her doll’s head down as hard as she could on Lemon’s foot.

Lemon jumped back from the tablecloth in alarm as Bea charged out from underneath, screaming.

“Daddy did not have a bad heart!” she cried. “You take it back right now!”

Bea used her doll as a battering ram, swinging at the woman wearing the lemon shoes. The woman’s wineglass tipped sideways, and a red fountain sloshed onto the carpet and Bea’s pajamas, but she didn’t care. The other grown-ups pulled away from her, staring.

A pair of strong hands gripped her shoulders, holding her down.

“That is enough, young lady.” Benjamin’s stern face loomed over her, and then her mother’s appeared next to it.

“Beatrice, what on earth?” Concern creased her mother’s forehead. “Why aren’t you in bed?”

Her mother reached for her, arms extending into a hug. But Benjamin whispered, “Get her out of here, Evelyn. She’s causing a scene.”

The arms froze halfway to Bea, then shrank back. The concern was rewritten as anger and embarrassment. “Of course, Benjamin,” her mother said. “Right away.”

Bea was crying so hard that the faces around her turned watercolory. Her mother shuffled her out of the room, making apologies to her guests. “Please excuse her. She’s not feeling well today.”

Once they were back in Bea’s room, her mother stood over her, frowning.

“That exhibition was embarrassing,” she said briskly. “I won’t tolerate such unladylike behavior. Benjamin has important business partners here tonight.”

“I wanted to see the party,” Bea started. “Everyone was dressed so fancy and—”

“What are you wearing on your feet?” her mother whispered, her cheeks graying. “Are those the shoes your father…” Her voice trailed away.

Bea looked down at her mother’s pale pink wedding shoes. She’d found them earlier when she’d been playing dress-up. She loved them. They were elegant, and she had wanted to be an elegant princess at the party.

“I was just trying them on,” Bea said. “They’re so pretty….”

Her mother bent down, staring. Bea saw it, too. A dime-sized dot of red wine across the toe of the right shoe.

“I’m so sorry, Mommy,” she whispered. “I—”

The slap came across her cheek suddenly, sharp and stinging.

“Don’t ever wear these shoes again.” Her mother’s voice broke, tears swimming in her eyes. “Never. And you are not to leave this room. Do you understand?”

Bea nodded, but she didn’t understand at all. When Daddy was alive, her mother had never even spanked her, let alone slapped her. There were no dinners where she didn’t belong. Only backyard barbecues and sticky fried-chicken fingers. Her mother had never used the word “ladylike” around Daddy. She’d never worried so much about other grown-ups before, either.

Bea crawled into bed and waited for a good-night kiss. It never came. Her mother left the room with the shoes, snapped the door shut, and locked it from the outside.

Bea’s tears trickled onto her pillow and away into the darkness. There was no prince coming to save her or her mother. Suddenly, Bea could feel the stillness overtaking her again, turning her into stone. It didn’t stop until it reached her heart, sealing it in cement for good.

RAY

Ray hadn’t banked on rain. It was only a light tapping on the bus’s roof when they crossed the state line into Tennessee. By the time they reached Nashville’s city limits, it was the sort of summer squall that brought driving walls of rain.

Her eyes were sandpapered with exhaustion, but she forced them to stay open as the lights of downtown Nashville appeared in neon rivers on the window. As soon as the bus pulled into the station, Ray nudged Pinny awake and grabbed their stuff.

She stepped into the aisle before the bus stopped, hurrying toward the door. Pinny moved more slowly, rubbing her eyes and yawning.

“Come on,” Ray said through clenched teeth. They had to get out of here before any cops came checking for missing persons, or their “friend” Ethel realized Daddy Dearest was a no-show.

Inside the station, Ray spotted a vending machine, fed two bucks into it, and grabbed two packs of peanut butter crackers.

“Here you go.” She tossed a pack to Pinny. “Breakfast.”

“We didn’t eat lunch or dinner!” Pinny protested. “Today is Sunday! Cheesy-macaroni day!”

“It’s one in the morning on Monday now,” Ray said. There was a freak-out coming, and she was so not in the mood for another holdup. “That’s breakfast.”

“I…I never miss cheesy-macaroni day.” Pinny sagged.

“Hey, you wanted to leave Smokebush, remember?”

“Yeah, but…” Pinny clutched her backpack like a security blanket. “Sundays, cheesy macaroni. Mondays, meatloaf. Tuesdays, chicken and biscuits—”

“I get the picture!” Ray snapped.

Pinny’s eyes toppled into panic, and sympathy overruled Ray’s impatience. Pinny had been so hell-bent on leaving Jaynis, but it was only a matter of time before reality kicked in. “Look,” Ray said, as gently as she could manage. “We’re sort of…over the rainbow now. Like Dorothy in Oz. So we have to be flexible about food.” She grinned and elbowed Pinny. “At least it’s not a bug burger from Fricasweet’s, right?”

Pinny giggled a bit. “I knew you thought their burgers were gross, too.”

Suddenly, Ray spotted an opportunity. Her life could be easier in a matter of minutes if only Pinny agreed…“You know,” she tried, “you can get on a bus back to Jaynis, no problem. You don’t have to stay.”

Pinny’s brow furrowed, her glasses slipping a frac

tion. “No way,” she said. “Face it. You’re stuck with me.” She took a deep breath, tearing open her pack of crackers. “Monday, crackers.” She stared at the water racing down the windowpanes of the station. “But…where are we going to sleep?”

Ray shrugged. “Not here.” She looked over her shoulder at Ethel, who was watching them with that Good Samaritan gaze. “I’ll find someplace. Let’s go.”

They pushed through the door and into the downpour, getting drenched within seconds. The rain hammered the streets as they started running. Pinny protested, but Ray ignored her. She cursed herself for not grabbing a city map while they were in the station, because now they were racing blindly through the deserted streets. Where could they go? The only places still open were bars; they’d never get in.

They turned corner after corner, until Pinny tripped, collapsing onto the sidewalk. Helping Pinny to her feet, Ray squinted through the rain to make out the sign on the lamppost above them: OPRYLAND DRIVE.

She’d heard of that….Suddenly, she remembered why.

“Come on,” she said, just as every light on the street blinked out. “I know where we can go.”

With a tremendous flash of lightning, the Grand Ole Opry lit up like a white fortress in front of them, an inviting shelter from the storm. The parking lot was empty, and with the power out, Ray thought they stood a chance of getting into the building without alarms blaring.

She led Pinny past the front entrance and around the side of the building, looking for some other way in. Finally, she spotted a door under an awning labeled ARTIST ENTRANCE.

She pulled out her pocketknife and jimmied the door. After a few seconds, a click reverberated up through her hand. She tested the handle, and the door eased open. She set a cautious foot inside and waited for sirens. But there was nothing but silence. The next flash of lightning illuminated wood-paneled walls and a sitting area.

“Where’s the stage?” Pinny whispered.

“We came in a back way,” Ray said. She rummaged through her duffel for the lighter she’d taken with Mrs. Danvers’s camping gear. She flicked it on and walked into another room filled with rows of mailboxes.

“What are those for?” Pinny asked.

“That’s where the Opry members pick up their mail,” Ray said. “The musicians, when they come to perform.” She’d read about it on the Internet. She wasn’t a fan of country music, but she’d always wanted to come here anyway. This was a place where nobodies became somebodies, and that counted for something.

She moved through the rooms on tiptoe, afraid that at any moment the lights would come on and they’d find a guard plowing toward them. When it didn’t happen and the minutes passed, she forgot they were trespassing. She forgot Pinny. She forgot everything…except music. Music had built this place, and she felt its thrum in the walls, its tendrils on the air, waiting to be given life.

When she found the auditorium, she stopped in the doorway as peace settled inside her. Surely, this was the way believing folks felt when they walked into church. The way people felt in the midst of something precious.

She walked past the rows of seats and onto the stage. Standing in the six-foot circle of wood on the center of the stage made Ray breathless, and her fingers craved to move. Her guitar was slick with rainwater, but she slid the strap over her shoulder, closed her eyes, and played. It was a melody she’d been working on for months, soft, slow, woozy.

She’d woken up humming the notes the day after she found out about Carter. She’d gone back to school thinking she’d see him again. He’d promised her as much that last afternoon at the lake. But she’d never expected to see him where she did.

On that first day back at school last September, she overheard Careena talking to Meg at the lockers.

“Have you seen the new music teacher?” she’d said. “He’s adorable. I heard he’s an ex-marine.”

Meg laughed. “Maybe I’ll pick up a new elective this semester.”

Ray rolled her eyes as she walked away, not thinking anything of it. But then, when she rounded the corner and saw Carter standing outside the office, a wrecking ball gutted her. Carter. They’d been talking about Carter.

In that second, the secret imaginings she’d kept close to her heart all summer, the sweet kisses she’d wished for, crumbled into reality.

She turned away, hoping he hadn’t seen her, but then he called her name. He walked toward her in those slacks and that button-down shirt that made him look older and her feel like a ridiculous child.

“Ray.” He smiled. “I was hoping I’d run into you.”

“So…you’re a teacher?” The word spat out like an insult.

“Crazy that they’re going to let me mold young minds, right?” He laughed, but then grew serious. “I got injured when I was deployed in Iraq two years ago, and I couldn’t go back. I…didn’t want to go back.” His eyes took on that glazed expression she’d seen before at the lake, the look of someone saddled with memories he didn’t want but couldn’t get rid of. Then he shrugged. “So here I am.”

She nodded mechanically. “You didn’t say anything….”

“I know,” he said. “I didn’t want to rehash it. And I didn’t want to spoil your lake for you either. Teachers in summertime…totally uncool.”

“Definitely.” She fell back on her smart-ass routine, hoping the tremor in her voice wouldn’t give her away. She’d spent the summer treating him like an equal. If she acted any different now, a red flag would go up. “If you’d told me, I would’ve kicked your ass.”

He laughed. “I believe you. But hey.” He leaned closer. “Don’t let the other teachers hear you say that. Spare yourself the detentions.”

His smile was the same easy one he’d had at the lake, but it was misplaced here under the fluorescent lights.

“So…maybe you’ll take my music-composition class this semester?” he asked. “Work on some new songs to play for me?”

Her mind said no. It said to save herself while she could. But her mouth answered yes. She wanted to be near him, every day, because there might still be a chance. She was stupid enough to believe in the possibility of his love. Screw taboo.

Her music knew better, though. The next morning, it had woken her up with the bittersweet melody she was strumming in the middle of the Grand Ole Opry stage right now. The song had tasted so sad in her mouth that the notes became a sound track to her tears.

PINNY

She knew Ray had forgotten about her. It wasn’t Ray’s fault. It was the music, and what it did to her.

The song sounded exactly the way Pinny felt when she thought of Mama—like she needed to cry, or laugh, or maybe both together. It made her glad she hadn’t gotten on that bus back to Jaynis. Ray had wanted her to. She could tell. Oh, she’d thought about it. All she had to do was say yes to the Life Plan. Horizons Assist had cheesy-macaroni Fridays. Mrs. Danvers had told her so. But then every day would be Fricasweet’s and Horizons Assist. That wasn’t enough. That’s why it made her itchy like a too-tight shirt. Even with a zillion jitterbugs fizzing in her stomach, even with the bigness of the world, the bigness of everything she didn’t know about, she was staying. And Ray’s song helped her remember why.

She clapped as loud as she could when Ray finished playing. When she did, Ray’s eyes flew open, and her eyebrows shot together like one long caterpillar.

“Stop,” Ray said.

“But it was good.” Pinny dropped her hands to her sides. “Way better than anything else you’ve ever played.”

Ray glared at her, and Pinny’s cheeks warmed. “I don’t play in front of anybody, except Ca—” She shook her head like she was hoping something she didn’t want in there would fall out. “I don’t play in front of anybody,” she said again. “You don’t know what I play.”

“Do too.” Pinny sniffed. Why did Ray argue so much? It was a puzzle. Especially when she was wrong, like she was now. “You played all the time at Smokebush. In the cleaning closet.”

“That’s none of your business,” Ray huffed.

“Then try playing softer.” Pinny shrugged and stood up from her seat. “Why do you write songs, anyway?”

Ray was quiet for a minute. “I guess I…I want to be heard.”

“That’s plain backward.” Pinny shook her head. “I hear you. But you just said that makes you mad. So you don’t know what you want.”

Ray laughed. “Maybe not.”

“See?” Pinny said, feeling proud of herself. “Everyone thinks I can’t pay good attention. Mr. Sands. Mrs. Danvers. In my Life Plan meetings, they talk about me. Not to me. But I know lots of things nobody else does.”

“Like what?” Ray sat down at the edge of the stage, with her legs dangling over the side.

Pinny grinned. “Mrs. Danvers keeps funny-smelling cigarettes in the shed at Smokebush. She sneaks out Sundays to smoke them. Careena throws up after lunch in the school bathroom. And I know that singing is your More.”

Ray stared at her. The caterpillar on her forehead was having a downright tantrum. “What are you talking about, my More?”

“Mama used to call it that. It’s not like having more black jelly beans. Mama said it was like…being Sunny-Side Up all the time. Like when Dorothy sings about the More that’s over the rainbow. With the lemon drops and happy bluebirds.” Pinny climbed onto the stage and settled down next to Ray. “Your face usually knots up tight, sort of pruny. But when you sing, it goes smooth and quiet. Like you believe in the More of things, same as me and Mama. That you’ll find it. And it makes you happy.”

Ray stared down at her feet. “I don’t believe in anything anymore,” she barked.

Pinny glared at her. “You’re lying. The More is why you got the Julie School book. It’s why Mama had auditions. Why I can’t work at Fricasweet’s. I think my More maybe has to do with Mama’s shoes. And I’m scared of it, too.”

Pumpkin Spice Up Your Life

Pumpkin Spice Up Your Life Shake It Off

Shake It Off Hot Cocoa Hearts

Hot Cocoa Hearts Sundae My Prince Will Come

Sundae My Prince Will Come Cake Pop Crush

Cake Pop Crush Donut Go Breaking My Heart

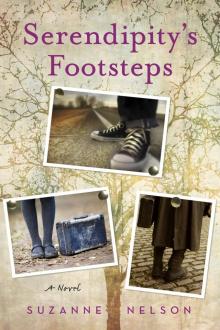

Donut Go Breaking My Heart Serendipity's Footsteps

Serendipity's Footsteps Macarons at Midnight

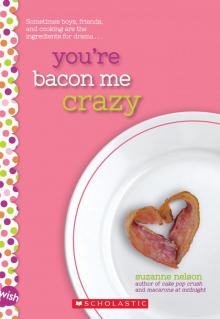

Macarons at Midnight You're Bacon Me Crazy

You're Bacon Me Crazy