- Home

- Suzanne Nelson

Pumpkin Spice Up Your Life Page 2

Pumpkin Spice Up Your Life Read online

Page 2

Daniel slapped his forehead. “Oh man, I zoned. Sorry. My bad.” He quickly set about making Brandon’s Heavenly Hazelnut Latte. But as I walked back around the counter to finish my lukewarm drink, I noticed how distracted Daniel seemed. Every few seconds, he glanced up, scanning the room for Kiya. When she finally met his gaze and headed in our direction, Daniel’s cheeks blushed anew.

“She’s walking over,” he whispered. There was a nervousness in his voice I’d never heard before.

Kiya was even prettier up close. She’d taken off her coat to reveal a stylish plum sweater and caramel suede leggings, and her hair, free of her hat, framed her face in tight dark brown coils. Every step she took exuded confidence, and her smile was open and friendly.

“You’re Daniel,” she stated when she reached the counter. “Marley said you’re the Mug’s best barista.”

Daniel opened his mouth but no sound came out. Finally, he managed a nod as he set Brandon’s Heavenly Hazelnut on the counter.

Kiya’s smile widened, and even Brandon blushed, until Elle nudged him and stuck out her hand toward Kiya. “I’m Elle,” she said. “This is my boyfriend, Brandon. And this is Nadine.”

“Hi.” I offered her a wave.

“It’s so great to meet you all!” Kiya said enthusiastically. “I’ve been freaked out about starting school tomorrow. We don’t know anyone here yet, so it will be such a relief to see some familiar faces in the hallways.” She turned to Daniel. “And I’ll be helping out here after school, so we’ll be working together. But I have to warn you …” Her laugh was bell-like. “I don’t know anything about coffee.”

After a second’s pause, Daniel at last found his voice. “No worries. When all else fails, just brew it.” He emitted a high-pitched, awkward laugh. I exchanged confused looks with Elle and Brandon. Since when did Daniel make cringey jokes? I glanced at Kiya, fully expecting her to roll her eyes at Daniel’s corny pun.

Instead, she gave a genuine laugh. “That’s cute.”

Was she for real? I tried to catch Elle’s eye so we could swap What parallel universe have we entered into? looks, but Brandon’s sudden “Ew!” averted my attention.

“Dude, what’s in this?” Brandon grimaced at his Heavenly Hazelnut. “It tastes sludgy.”

Daniel took a sip from Brandon’s outstretched cup. “I must’ve put soy milk in. Sorry.”

I glanced at Daniel worriedly, wondering if he was coming down with something.

And then I got my second shock of the day.

“Nadine?” a familiar voice said, and I turned to find my father standing behind me.

“Dad?” I was rattled. My dad hadn’t set foot in the Snug Mug since my mom had left. Marley had once told me that Mom used to come here all the time, armed with travel guides to plan trips she and my dad would never actually take. I couldn’t blame my dad for not wanting to come back. In fact, he looked pained to be here now, his face drawn, his lips pressed together. “What’s wrong?” I asked.

“Nothing’s wrong.” But he squirmed, fiddling with the zipper of his vest. “I need to talk to you about something.” He brushed a hand through his graying hair. “At home.”

My pulse quickened. “Um, sure. Okay.” Daniel gave me a questioning look, but I could only shrug. I didn’t have any idea what this was about.

“I’ll see you guys later.” I grabbed my cello, offering my friends an uncertain wave as I followed Dad out the door.

I sat at the kitchen table as Dad ladled Crock-Pot chili into two bowls. The quiet of our two-bedroom cottage was a heavy and sustained caesura around us.

Dad was sort of like a rabbit, sometimes poking his head out of his warren, but retreating if he sensed the smallest shift in the wind. He took me to the doctor when I was sick, and made sure he kept the kitchen stocked with my favorite snacks for packed lunches. When he noticed how much I loved classical music, he’d rented me a used cello and gotten me private lessons with Maestro Claudio. He cared about me. He just didn’t say it aloud.

More often than not, Daniel came over to our house for dinner. I’d started asking him over because he livened things up with his jokes and laughter. After we ate, we’d do our homework together. Daniel’s mom worked long hours as an ER doctor at the hospital in Rutland. Since Daniel’s dad had died, his mom couldn’t handle being home too much, so she escaped into her job. She had the same look of vacant loneliness that my dad did. Maybe that was why Daniel and I had become best friends years ago. We were two only-child magnets clinging to each other for the company we couldn’t find in our own families.

But Daniel wasn’t here right now, and, as Dad sat down facing me, I wished he were. Dad didn’t look like he was enjoying our current awkward silence any more than I was, and spent an inordinate amount of time fishing around in the box of oyster crackers.

“Isn’t it a little early for dinner?” I asked, attempting to start the conversation.

“Is it?” Dad remarked absently as he sprinkled crackers into his bowl.

“It’s only four thirty.” I gave a small laugh that ricocheted around the kitchen.

“Oh. Right.” He scratched at the back of his neck. “Sorry. I’ve been distracted.”

I took two half-hearted bites of the chili, and then I couldn’t wait anymore. “What’s going on, Dad?”

He stared into his bowl. “It’s about your mom.” He met my eyes tentatively, then looked toward the front door, probably mapping out an escape route.

My heart dropped. “Is she okay?” A small voice inside my head said that I shouldn’t care, since I hadn’t seen her for six years and hadn’t heard from her in months.

Mom had found her grand adventures and sidewalk cafés, but she’d done it half a world away from us. Occasionally, she’d send emails from remote corners of the planet. “You’ll never guess where I am,” they usually started, with a “You must be so big by now!” thrown in for good measure. Then there were the souvenirs that arrived in the mail sporadically, from places I’d never even heard of, like Tristan da Cunha or the Siwa Oasis. She never stayed in any one place for long, and some spots she traveled to were so remote that she couldn’t stay in touch easily (or so she said). I made a conscious effort not to think about my mom often, as a matter of self-preservation.

“She’s fine,” Dad said. “In fact,” he continued with forced brightness, “she’s moving back to the States. Just outside of Boston.”

“Really?” I tried to make it sound offhanded, like it didn’t matter where she lived, since she’d backpacked herself out of my life anyway. “Why?”

Dad swirled his spoon around his chili. “She’s gotten a full-time job, working with refugees at Save the Children.”

“That’s cool,” I said quietly, meaning it. Mom was always volunteering wherever she trekked to, working with aid organizations to build houses or dispense food and clean water. Working with refugees sounded right up her alley. “Is that what you wanted to tell me?”

Dad hesitated. “She’s asked if …” His voice faltered. “She’s asked to see you.”

“What?” My spoon clattered into the bowl. My throat burned with a rising anger. “Are you kidding? After all this time?”

Dad rubbed his forehead. “I’m as surprised as you are. When you were smaller, I hoped she would try to …” He cleared his throat, then tried again. “She was barely twenty when we had you. She hadn’t seen anything of the world yet, and—”

“I know.” I rolled my eyes. “She had an irresistible wanderlust.” I stood up to dump my uneaten chili into a Tupperware container for later. “You’ve been making the same excuse for her since I was in second grade!” I spun to face him. “You were as young as she was. And you didn’t leave!”

Dad sighed. He worried his napkin, rolling and unrolling its edges, and I could tell he wanted to dive back into the safety of his warren. He stood and stuck his chili in the fridge. “I’m going to the lab for a while.”

Dad was an arborist who specialized in r

are tree diseases. He worked at one of the University of Vermont’s satellite offices, studying Woodburn’s elm trees. But he hardly ever went back to the lab after I got home from school. He was using the lab as an excuse to escape, but I didn’t call him on it. I was ready to drop the subject, too. But Dad paused at the front door, his expression so wretched that my heart panged.

“Maybe consider it?” he asked, and I shook my head.

“Consider it? Did she consider me when she walked out?” His face sagged further, but I headed for the stairs that led to my bedroom. “I don’t want to see her,” I said flatly. “Not now. Not ever.”

As I expected, my words were met with silence, followed by the soft click of the front door shutting. I paused on the stairs, my heated resolve dissolving into confusion. Taking out my phone, I typed Code Red and let the text fly. Daniel and I had used the term ever since we were little. It meant, “Drop everything and run—do not walk—to your BFF no matter the hour or place.” Neither one of us had ever ignored a “Code Red,” and I knew Daniel wouldn’t now. So I sank onto the bottom step, waiting for his reply.

An hour later, I hurried back into the Snug Mug with my cello in tow. The afternoon’s crowd of after-schoolers and leaf peepers had been replaced by the more serious coffee shop set—the aspiring writers, grad students, and angsty artists. Sometimes, the shop held poetry readings or spontaneous acoustic guitar performances. Tonight, though, the shop was filled with the quieter hum of low conversations accompanied by the welcome fizzing of the espresso machine’s milk steamers.

I glanced behind the counter, but Daniel was nowhere to be seen. Marley caught my eye over the top of the espresso machine, then nodded toward the loft. “He’s upstairs.”

I thanked him and climbed the stairs to find Daniel sitting on the loft’s threadbare couch, waiting for me. The loft served as Marley’s office, but aside from the haphazard mounds of receipts and files piled in one corner, it wasn’t much of an office at all. More often than not, Marley could be found napping in the corner hammock as he listened to the Doors on his vintage turntable. Shredder liked to nap on the couch, and Daniel and the other Snug Mug employees used it as a makeshift break room. The loft was where Daniel and I had learned to appreciate the priceless crackle of old vinyl records and also where we went whenever we needed to talk away from the café chaos downstairs.

Daniel jumped up, and relief washed over me when I saw that his strange Kiya-induced delirium was gone.

“God, Nadi,” he said, opening his arms. “This is some Code Red.”

I sank into his hug, grateful. Daniel’s hugs were always enveloping, showing how much he cared. They were one of his many awesome BFF qualities.

“I have reinforcements.” He motioned toward the rickety coffee table; there was a plate with a waffle on it, plus a mug of Pumpkin Spice Supreme, both heaped with clouds of whipped cream. The waffle was also topped with Teddy Grahams, toasted marshmallows, and chocolate syrup.

Even though I was still reeling from my dad’s news, an involuntary smile spread across my face at the sight of the waffle. “Is that what I think it is?”

“Nadine’s Song.” He propped my cello in the corner and set the waffle plate in my hands. “It got us through the first Code Red, didn’t it? So I figured …”

“Thank you.” I plopped down on the couch and took a grateful, heaping bite, relishing the crispy, caramel sweetness of the waffle combined with the gooey, warm chocolate and whipped cream. The memory of the first time I tasted this waffle came back to me. It was on the night after Mom left. I’d had enough of putting on a brave face for my dad, who’d been trying (and failing) to act like everything would be fine. So, I’d retreated to my bedroom with my cello.

Soon, my by-the-book practicing turned into my discovery of a new, mysterious melody on the strings. I got lost in the song I was composing, and that was when seven-year-old Daniel wandered into my bedroom with a thermos and a plate full of misshapen, undercooked waffles.

“Omma is downstairs talking to your dad,” he’d said, using, like he always did, the Korean word for “Mom.” I’d quickly put away my cello, embarrassed that he’d heard me playing a nonsense song. “She says I better not say anything to make you cry.”

“I’m not going to cry,” I told him stubbornly. Even though I’d been secretly crying on and off in my bathroom all day, I didn’t want to admit it.

He scooted onto the bed beside me, and our feet, which couldn’t yet reach the ground, started swinging in unison. “That was a pretty song you were playing. What was it?”

I shrugged. “I made it up.”

“You’re a composer.” He nodded appreciatively. “Cool.”

He said composer so matter-of-factly. And the moment he said it, the truth of it solidified inside me, a pearl of purpose that made the awfulness of what had just happened a little more bearable. A composer, I thought, that’s what I am. And from that day forward, I was.

“I brought some hot chocolate,” Daniel had said then, holding up the thermos. “And Omma cooked a batch of samgyetang for you and your dad. It’s her special Korean ginseng chicken soup. It’s good, but I thought you might like these better.” He set the plate of waffles in my lap. “According to my mom, waffles were the only thing I wanted to eat after my dad …” He glanced down at his feet, which stopped swinging. “I thought they might help.” He pointed to the Teddy Grahams and marshmallows atop the waffles. “I added stuff to make it extra sweet …” He smiled. “Like you.”

“Thanks.” I took a bite. “It’s really good.”

“It can be your special waffle.” He thought for a second, then glanced at my cello. “We can call it Nadine’s Song?”

I laughed. “Sounds pretty fancy for a waffle.”

“It’s perfect.” He nudged my shoulder. “We’re both missing parents now. They’re just gone to different places.” We sat with that for a minute, and then he added, “It’s going to be okay.”

I blinked back tears. “How do you know?”

“Because we have each other,” he’d said. And he’d been right.

Everything had been okay, relatively speaking, until tonight. Now I opened my eyes to find Daniel dipping a fork into the other side of my waffle, and I playfully tried to shove his hand away. But of course, I let him swipe a huge bite.

“So,” he said as we both dug in. “Tell me the whole story.”

He listened intently as I vented about the many, many reasons why it was completely unfair of my parents to railroad me with this.

“Especially right now,” I finished. “Don’t they get how huge this Interlochen audition is for me? I can’t afford distractions. But I have to deal with being guilted into seeing my mom!”

Daniel stared at the smear of whipped cream swirled on the now-empty plate. “I’m not sure they’re guilting you into it,” he said quietly. “They’re testing the waters.”

I balked. “It’s total manipulation!” I drained the last of my latte in one furious gulp, which made Daniel laugh.

“Maybe I should’ve made that decaf,” he joked, but then his expression turned serious. “Nadi, you have every reason and right to be angry, but I wonder …” He ran a hand through his dark brown hair, making a few waves fall into his eyes. “I just think about my dad sometimes, and how I would give anything to have had more time with him.”

My heart squeezed at the mention of his dad. “I know,” I said softly, “but your dad didn’t make a choice to leave. My mom did. Your dad loved you, and my mom …” My voice cracked as hurt rose inside me. “I’ve made up my mind.” I straightened my shoulders. “Let’s not talk about it anymore, okay?”

Daniel seemed on the verge of saying more, but he nodded. He stood up and retrieved my worn cello case. “So … am I going to hear your tour de force or what?”

“I thought you’d forgotten about it,” I said, already sliding out my cello and bow. My rented cello was as tired-looking as its case, and it bore the scars from its prio

r players’ misuse. I dreamed of having my own cello someday, and I saved as much babysitting money as I could, but it would be a long, long time before I could afford one. Now I brushed a hand over the weary cello, wishing I could coax it into giving me the rich tone I wanted to hear whenever I played. Then I looked at Daniel. “You know, you were sort of spacey earlier today.”

“Oh, Marley’s news threw me, that’s all.” His tone was casual, but even in the loft’s dim light, I saw his blush. He motioned to my cello. “Let’s hear it, maestro.”

I thought about bringing up Kiya, and how entranced he’d seemed by her. But why should I when Daniel said it was no big deal? Besides, I was finally getting the chance to play for him, and I’d been waiting for it all day.

“Here goes.” I sat down in Marley’s straight-backed office chair and raised the bow to the strings. My piece was a prelude with slow-moving slurs. As I played, my eyes closed, and then the magical moment happened—the moment that had made me fall in love with the cello in the first place. The music moved from the cello and through me, until we were both filled with never-ending notes.

As I played the final note and lifted my bow from the cello’s neck, the world gradually rematerialized around me.

Daniel was staring at me, wide-eyed.

I shifted self-consciously. “Was it awful?”

He didn’t have a chance to answer before clapping and whistling erupted from the customers downstairs. “Encore!” Marley’s voice shouted up to me.

I blushed and tucked my head against my cello’s neck. “Omigod, everyone was listening.”

“It would’ve been hard not to.” Daniel smiled. “That piece was phenomenal.” He leaned toward me, his eyes bright with pride. “You are going to be the next Interlochen summer camp prodigy. You’ll see.”

“I hope so,” I whispered, my stomach tightening with nerves.

Just then, our phones buzzed simultaneously.

Daniel got to his first. “It’s Omma, telling me to come home.”

Pumpkin Spice Up Your Life

Pumpkin Spice Up Your Life Shake It Off

Shake It Off Hot Cocoa Hearts

Hot Cocoa Hearts Sundae My Prince Will Come

Sundae My Prince Will Come Cake Pop Crush

Cake Pop Crush Donut Go Breaking My Heart

Donut Go Breaking My Heart Serendipity's Footsteps

Serendipity's Footsteps Macarons at Midnight

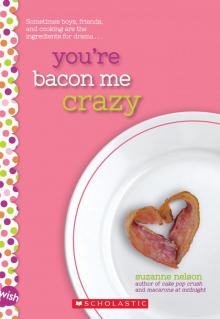

Macarons at Midnight You're Bacon Me Crazy

You're Bacon Me Crazy