- Home

- Suzanne Nelson

Serendipity's Footsteps Page 4

Serendipity's Footsteps Read online

Page 4

Dalya nodded, thinking of the Gestapo that kept them here, living like animals in filth and squalor. But because she didn’t know how to answer Frau Scheller’s comments about Aaron, she said instead, “Tell Muti I’ll keep Inge safe, as best I can.” She vowed she would, for as long as possible.

But on the third day in the infirmary, Inge stopped eating. The soup ran down her chin, pooling in the hollow of her neck. Even Frau Scheller was at a loss for encouraging words.

On the sixth day, Dalya woke with a shudder, alone. She blinked against the icy glare of the windows and knew, when she pressed her hand against the cold, rough fibers of the cot, that she’d been sleeping alone for hours.

A nurse standing nearby peered over her chart at her. “It’s back to the barracks for you,” she said flatly. “The doctor says you’re well, and strong enough to work alongside the other women. The guards will give you your orders.” She jerked her head toward the door at the other end of the infirmary, and Dalya stood, the question that she dared not ask singeing her tongue.

She walked haltingly, not wanting to leave without knowing for certain. But then she caught sight of Frau Scheller tending to another patient along the wall. Their eyes met for a brief moment, and Frau Scheller nodded, her face barely masking her sadness. Dalya’s eyes filled, but she would not let a single tear fall, not in front of the guards and doctors, who looked on with interest, as if she were some experiment in grief.

She found her mother in the barracks, huddled against the wall of their bunk, waiting to hear what her heart already knew was true. Her mother glanced at her, standing alone before her, and the question was answered. A howl ripped the air, piercing Dalya’s heart, freezing it in that moment.

After that, winter settled in her bones, and there was no warming them. But still, she sketched her shoes. Now she didn’t sketch them to stay warm. She sketched them to stay alive.

RAY LANGSTON’S BEGINNING

The mother crawled away from the heap of twisted metal. Her vision was coming and going in waves, but she’d made out the call box across the street, and she needed to get there.

The strained crying of her daughter rose in the air, and she welcomed it. The crying was strong, healthy. So much better for the baby to be crying when silence would only mean one thing. When she’d looked over at her husband in the front seat, right after the tire of the semi came through the windshield, she’d seen silence etched on his face. She’d known it was no use calling out to him. He was gone even before the car stopped spinning on the road.

That’s it, sweetie, she urged Ray as she dragged herself across the icy street. Keep up that hollering. Let the world know we’re here.

Before she’d climbed out of the smashed window, she’d checked the backseat and nearly laughed with relief at her rosy-cheeked Ray sitting untouched in her car seat, her sage-green eyes quizzical and calm. But the heavy pain in her chest had stopped her short.

Daylight was dimming as she reached the call box, and with her last bit of strength, she dialed 911, then collapsed into the brittle grass. Soon, joining with her daughter’s cries, the wail of sirens sang out. She smiled and gathered all her love, sending it out toward the shattered car and her daughter, hoping it would find its way to her on the wind.

You’re going to be fine, Ray, she thought. Just keep making noise.

It was then that she saw the running shoes. Her husband’s—silver with neon-orange laces and treads. They were strewn across the yellow center line in the asphalt, a good twenty feet from the wreck. One shoe had landed upright, the other lay on its side.

How funny, she thought. They look lonely.

Then a curtain lowered over her eyes, and the perfect world that held her daughter slowly ebbed away.

DALYA

Dalya didn’t know what she was building, but she didn’t care. The sleet that had been falling all morning had stopped, and an alabaster sun was breaking through the clouds, warming her chapped, blistered hands. She pushed her wheelbarrow of broken slate along the crackling, frozen ground, then dumped its contents onto the curved track along the perimeter of the roll-call yard. The track was made up of different sections—sand in one, rocks in another, gravel in another. She’d been building it for weeks, alongside the other able women in the camp. It didn’t make any sense, but then, nothing in the camp did. She didn’t expect it to anymore.

She heard a small cry and glanced over her shoulder to see her mother stagger behind her brimming wheelbarrow. She tripped and fell to one knee, and Dalya took a step toward her, then stopped when her mother waved her away.

“Don’t,” her mother scolded, hoisting herself up again. “You know they’re watching. I’m fine.”

Her mother was right. The guards were always watching, waiting for prisoners to falter so that they could dispose of them. And her mother had been coughing for weeks, just like Inge had before the end. Dalya sometimes wondered if her mother had given up when Inge died. Her eyes were dull and void, unbearable to look at. For now, though, her mother was still standing, still working. That was what kept her safe.

Dalya tilted her head toward the blue sky, soaking in the sun’s rays. She could almost smell the earthy sweetness of grass twining up from the dirt, of honeyed blossoms opening on waking tree limbs. Beyond the camp’s barbed wire, somewhere, life was in bloom.

—

One week later, she saw her father walking on the track she and her mother had made. A steady rain fell as she finished roll call, and her head was clouded with visions of the shoe she’d been drawing on the barrack wall earlier. Her mother gripped her arm hard enough for her to flinch, and that was when she looked up to see him. Her father was with a group of thirty or so men and older boys, all wearing heavy combat-style boots. Aaron was beside him, but there was no sign of David or Herr Scheller anywhere. It had been months since Dalya had seen either of them, and as she watched the men now, Aaron caught her eye.

The shake of his head was almost imperceptible, and she wanted to believe she hadn’t seen it. But the sorrow in his face was undeniable.

She longed to cry, but found that her eyes were too weary for tears. Instead, she held on to her mother, watching the men and boys form military-straight lines on the track.

“What are they doing?” she asked.

Her mother stared for a long time. “Shoe testing,” she said quietly. “I heard the guards talking last week. The boots come from shoe factories. The men in the Schuhläuferkommando are meant to test the quality.”

Soon, Dalya saw what “testing” meant. A guard blew a whistle, and the men began marching around the track, through the slate and sand and rocks Dalya had helped lay down.

The marching itself might not have been so awful, but even from a few hundred feet away, Dalya could tell by the men’s posture that there was something wrong with the boots. The men were stooped, their legs bent oddly, their feet anchored too far apart or too close together. Dalya had learned how to tell when a shoe was ill-fitting. Her father had always told her that a well-made shoe makes a man walk taller, chest angled toward the sky. These shoes, she decided, were much too small for the men.

Dalya winced as Aaron’s face beaded with sweat and her father’s tightened with pain. They marched all through the morning until, suddenly, a man toward the front of the line collapsed.

Almost before the man hit the ground, the shots rang out. The guards dragged him away, leaving behind a pool of blood, seeping into the gravel.

Her father and Aaron were not shot. They kept walking.

At noon, they were each given a large sack to carry. Dalya knew it must be heavy, because one elderly man buckled to his knees as soon as it was placed in his arms. Her father and Aaron did not collapse. They stood, unwavering, the sacks in their arms.

Then they ran. Holding these enormous sacks, they ran without stopping for food, water, or rest. At some point, Dalya’s mother left, unable to bear it. But Dalya stayed. She couldn’t look away. And then it happened.

/>

Her father lost his footing and started to fall. Dalya’s heart shrieked as a guard aimed his rifle at her father. Her mouth couldn’t utter a sound. But Aaron, with lightning speed, shifted his sack to one arm and reached for her father’s elbow with the other. Barely the brush of a touch, it was enough to brace her father, to straighten him up. It was enough for the guard to lower his rifle, and for Dalya to catch her breath.

She could hear some of the men crying as they ran. Aaron didn’t cry. Neither did her father. Her father, whose life had been shoes, whose goal had been to make shoes comfortable for every person, bore the burden of these boots of torture silently. Her father, whose daughter had made the track on which he shredded his feet, surely now bleeding inside the boots, ran on the track until the sky dimmed into dusk. Until, at last, he was taken off the track and led away.

—

The pebbles raining down on the barracks’ roof were a message meant for her. She’d never left her bunk after dark before. It was forbidden, and she shuddered to think of the punishment if she were caught. She waited a few minutes, through another storm of pebbles, and then her body made up its mind for her, and her feet slid out of the bunk of their own accord, walking to the door.

The night air stung her cheeks as she stepped outside, but it was the glittering veil of stars draped across the sky that took her breath away. She was so entranced that she nearly forgot where she was until she heard a low owl call. She checked for guards but didn’t see any. She eased nearer to the fence. A shadow, the right size and shape for Aaron, pressed up against the wall of the men’s barracks.

He stepped toward her, his eyes glinting with starlight, and she noticed his awkward limp, even in the darkness.

“How bad are your feet?” she asked.

“Not as bad as the others’. They’ll heal.” He edged closer. “We only have a few minutes. The guards are playing cards, but it won’t last long.” He glanced up at the sky. “Isn’t it amazing? So much beauty up there, and so much ugliness down here.”

Dalya nodded. “It doesn’t seem fair that somewhere, someone else is watching the same sky. But they’re free.”

“I know.”

They stood silent for a few moments, the clouds from their breaths floating upward until she imagined them mingling with the stars.

Then Aaron asked, “Do you ever wonder what you would be like if you’d been born to belong on the other side of these walls? If you had a different God and different choices to make?”

“You mean if we weren’t Jewish?” Dalya whispered.

Aaron nodded. “Do you think the hatred would come naturally, or would you question it?”

Dalya’s stomach tightened, and she stared at his face, wondering what she’d see in it if it weren’t masked in shadow. “I don’t know. I never thought about it that way. I suppose if that’s all they taught me, if that was the truth I knew, I might believe it.” She flinched, repulsed by the idea of being so corruptible. “Would you?”

“I hope not,” he said. “I used to think that truth and right were the same. Not anymore.”

He whipped his head around, and Dalya heard faint voices in the distance.

“They’re coming,” he said. “You better go.” She nodded and began to back away, but then he motioned for her to wait.

“Dalya, I need to tell you something….” His voice was heavy, and the weight of it made her feel the consuming pain of what was coming. “I’m sorry, but you won’t ever see your father again.”

“I know,” she whispered, hugging her arms to her chest. It was like Aaron had said. Nothing about that horrible truth was right. But she’d have to carry its certainty with her forever.

RAY

After the horrible thing happened, Ray knew she would run, like she had so many other times. She’d already been running for the last fifteen minutes since she left the school gym. Sweat seeped through the bodice of her dress and coursed down her cheeks, mixing with her tears as her feet staccatoed the pavement. Still, she kept running.

Her feet should have been hurting. They always did, even with feathery, tiptoe steps. But they didn’t right now, or if they did, she couldn’t feel it. She only felt one thing: the need to run. This time, though, she would run so far no one would ever find her. She’d run to a place where she could get lost forever, where she could fade into the sidewalks and alleyways without anyone noticing the girl with the limp and the charred-black hair.

In the moonlight, she could see that her cherry-red dress was sweat-stained and gray with dirt. It had been so beautiful when she’d first glimpsed it on the rack, but now she hated the sight of it. She couldn’t believe she’d ever thought it would make a difference, that it could make Carter think of her as anything other than what she was—a complete waste.

The dim outline of the Smokebush buildings appeared against the darkness, and Ray stopped in the shadows of the Spanish oak. It was only a temporary stop. She’d get in and out before anyone saw her, especially Mrs. Danvers. She yanked at her dress violently until the satin fabric gave way, freeing her. Grabbing her pocketknife from the hollowed-out knot in the tree where she kept it, she slashed the dress into stringy threads. She hurled it into the creek. It landed softly, raising the reedy pitch of the water by a half step, billowing like a spidery flower. Then the current sucked it under, and it was gone.

Ray slipped the pale pink shoes off next, and cocked her arm back, ready to launch them into the water, too. But they glowed ethereally in the moonlight, and Ray hesitated, feeling their mysterious pull just as she had the first day she’d seen them in the Pennypinch. No…she should let them drown. Everything that had happened tonight was because of them. It was their fault, and she hated them for it. Still, though, if it was possible for shoes to look pleading, these did. As if they were straining toward survival, as if they’d been built that way.

She closed her eyes, tensing every muscle, but her fingers wouldn’t let go of the shoes.

She swore, then ran to the Dumpster beside the main building and tossed them on top of the garbage.

An instant pity and longing for the shoes struck her, but she ignored it, climbing up the oak and into the open window of her second-story bedroom. She slunk past her sleeping roommate, Nancy, thankful she snored so loudly, put on her jeans and holey Carole King shirt, and shoved a few clothes from their shared dresser into her duffel. She pulled on her sneakers, wincing. She kept hoping she’d get used to it, or the nerves in the scar tissue would deaden. But it always felt the same, like a thousand hot needles piercing her skin.

She gritted her teeth against it, grabbed her guitar from the corner, and made her way down the hallway toward Mrs. Danvers’s office. The door was locked, as usual, but Ray used the spare key (the one that Mrs. Danvers had “lost” years ago). The office was as cluttered as ever, the desk crammed with paperwork, but Ray knew exactly where the petty-cash envelope was. She’d never taken the entire thing before, only skimmed off the top. Tonight, though, she folded all of the crisp bills into her pocket.

“Sorry, Mrs. D.,” she whispered into the darkness.

She turned around, then gasped as she slammed into a thick wall of softness blocking her way, and a sudden flash of red patent leather peeked out from the shadows.

“Pinny!” Ray hissed. “What are you doing in here?”

“Spying on you,” Chopine whispered matter-of-factly.

Ray yanked Pinny into the office and shut the door so no one would hear them. “When did you get back from the dance?” Ray asked, wondering if Pinny had seen her there tonight and if she was about to get hit with a dozen questions about what had happened. The look of staunch determination on Pinny’s face made Ray nervous. She’d seen that look in Pinny’s eyes before, mostly when Pinny was hogging the TV in one of her Wizard of Oz marathons. She’d watched the movie a hundred and thirty-two times (she kept a running tally). One time, Nancy dared turn it off mid-Munchkins, and Pinny had rewarded her by stalking her, singing “Follow

the Yellow Brick Road.” It only took an hour for Nancy to beg for mercy. No one ever came between Pinny and Dorothy’s ruby-reds again.

Now Pinny shrugged. “I’ve been back awhile.” There was a rattling, followed by the sound of chewing and the smell of licorice, and Ray knew Pinny must be eating one of her endless bags of black jelly beans. “You’re running away.” Her voice was gummy with the candy. “I’m coming with you.”

Ray smirked. She had to admit, Chopine always surprised her. Everything from her name to the glitter-laden purple Keds she wore every day was a contradiction.

“I’m not going anywhere,” Ray lied. “And neither are you. I don’t want to get stuck with bathroom detail…again. You don’t either.”

Chopine tilted her head, studying Ray. “When you lie, your eyes go weaselly.”

Ray groaned as panic clamored through her. She did not need this holdup. She had to be on a bus out of town before Mrs. Danvers realized she was gone. Otherwise, someone would come to drag her back to Smokebush. With her luck, it’d be Sheriff Wane. Oh, the pleasure he’d have on his greasy, pockmarked face when he found her. He’d had it in for her for years. Last week, when he’d caught her tagging the wall outside the Wiggly Pig grocery for the hundredth time, he’d said as much.

He’d surveyed the trail of notes she’d sprayed so far, a curving slur of arpeggios in G—the beginnings of a new song she was writing. Then he spit a stream of chew at its base. “If you’re going to end up in juvie,” he said, “at least make it for something better than this trash.”

Well, she wasn’t about to give him the satisfaction of nailing her tonight.

“Pinny, just…go to bed!” Ray hissed.

“No!” Pinny folded her arms. “You’re going to New York City, and you’re taking me.”

Ray sighed in irritation. “How do you know I’m going to New York?”

“Because you ordered that book from the Julie School there.” Pinny spoke in a fuzzy legato, her teeth never quite grabbing the words. “You did it from the computer in the common room. And you hid the book. In that hole in the tree outside. I saw you put it there.” She smiled triumphantly. “I’m a good detective.”

Pumpkin Spice Up Your Life

Pumpkin Spice Up Your Life Shake It Off

Shake It Off Hot Cocoa Hearts

Hot Cocoa Hearts Sundae My Prince Will Come

Sundae My Prince Will Come Cake Pop Crush

Cake Pop Crush Donut Go Breaking My Heart

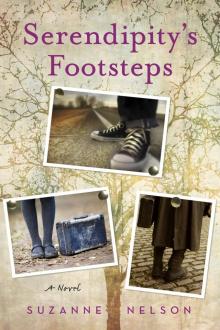

Donut Go Breaking My Heart Serendipity's Footsteps

Serendipity's Footsteps Macarons at Midnight

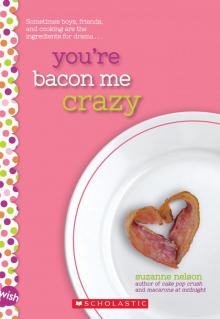

Macarons at Midnight You're Bacon Me Crazy

You're Bacon Me Crazy